99% of all internet traffic from this Article to your Pokemon Go account to your family WhatsApp group runs on a hidden network of undersea cables. Why should you care? Modern life is increasingly dependent on those slinky subaquatic wires, and they get attacked by sharks from time to time. How do they work? What’s the future for them? Join us today as we plunge into the depths and ask how the internet travels across oceans.

Submarine Cables

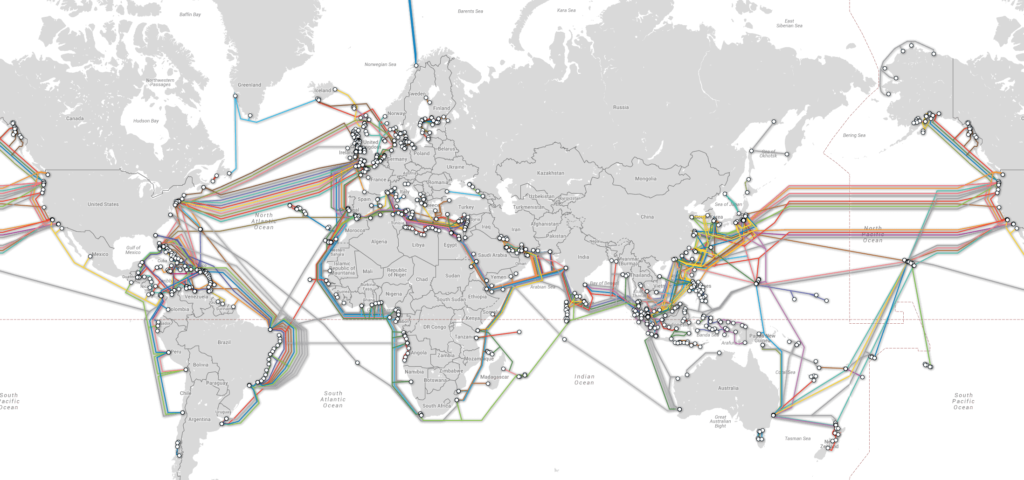

according to the authoritative submarine cable map website, there are currently 493 active or actively under construction sub-sea internet cables criss-crossing the globe; these range from the relatively modest 300 kilometers Azerbaijan to turkmenistan wire running under the black sea to the huge 6600 kilometer Maria cable linking virginia beach in us with bill bow in northern spain maria weighs the same as 24 blue whales the firm’s laying down this serpentine superhighway worldwide there’s now 1.5 million kilometers of undersea data wires arcadey about how much it all costs

But professional estimates indicate a typical transoceanic cable should set you back between three and four hundred million dollars, which seems like a lot because they’re not especially thick, typically around the girth of a garden hose, and that includes layers of protective thixotropic jelly around the all-important fiber optic core plus multiple plastic sheaths and copper wiring to power the thing but even so on average they can ferry an awesome 100 gigabytes per second in data with newer and forthcoming cables able to transmit 400 gigabytes per second.

How Do They Work

so how does so much data fit down such slim channels? Part of the answer is a highly sophisticated data wrangling technique known as dense wavelength division multiplexing; put, dense wavelength division multiplexing lets data providers use more than one wavelength of light to convey information fiber optically instead, several wavelengths are employed simultaneously and stacked, creating astonishing data speeds.

This happens at buzzing data center-like landing sites at either end of the cable. Are the cables just straightforward long wires not quite every 70 to 100 kilometers or so along the seabed cables are punctuated with so-called repeaters; these essentially serve as amplifiers, keeping the signal strength up to par over long distances; that’s why the wires incorporate copper conductors by the way carrying up to 10 000 volts of dc to power the repeaters.

How are the cables late? They’re first coiled into vast cylindrical drums on specialized cable laying ships; as much as a year’s planning and charting will go into plotting the perfect trans-oceanic route; wrong locations for undersea cables include anywhere volcanic or anywhere, especially earthquake or mudslide-prone or anywhere heavily trolled by fishermen the cable is spooled out the back of the ship at a sedate pace of around 10 kilometers an hour.

If the ship encounters bad weather, the captain can decide whether to break off the cord, tie it to a boy, and retreat to karma waters; when the storm passes, the ship returns to the boy and picks up where it left off, accidents and outages on the cables can and do occur.

In 2012, Hurricane Sandy in the u.s knocked out several critical transatlantic cables, disrupting networks for hours.

In 2011, the Fukushima earthquake in Japan caused similar online The vast majority of such disruptions, however, are the result of human carelessness; typically, trawler nets or wayward ship anchor cables situated close to the shore are significantly more at risk from such disruption; as such, the nearer to lander cable is the more likely it’ll be carefully armor-plated many are even dug into the seabed in long dedicated trenches carved out using ship-drawn plows awesomely sharks have been spotted nibbling on one of google’s subsea cables get your teeth into this 2014 clip.

More sinister even than that, the us government has consistently warned of interference in the cables from hostile foreign powers like Russia or China. The US government should know all about whistleblower Edward Snowden, who revealed in 2013 how the NSA had no qualms about eavesdropping on fiber optic communications.

The geopolitical implications of undersea cables are also fascinating. Last year, the Australian government intervened to prevent Chinese technology giant Huawei from installing a cable connecting Australia with the Solomon Islands. The fear is that China could use the link to access Australia’s sensitive internal networks.

Who Owns This Cable

So, who owns these cables? That’s an interesting question. It’s an expensive business, so historically, nations or quasi-national telecom providers have picked up the bill.

The world’s biggest cable owner remains America’s AT&T, with a stake in some 230,000 kilometers of underground cable.

The second biggest owner is China Telecom. Frequently, cables are owned by groups or consortia of up to 50 separate owners, including tech firms, local government agencies, and other businesses. While this model helps spread the initial cost, it’s less helpful when something goes wrong, and nobody can agree on who has to put on a wetsuit and do something about it.

Increasingly, big tech is recognizing its scope for growth is limited by the undersea cable network, so over the past few years, the overwhelming majority of investment in undersea cable infrastructure has come from companies like Facebook, which currently owns nearly 100,000 kilometers of cables, google owns roughly the same amount Amazon has its massive private network hooking up the online giant’s mighty aws data centers through cables traversing the Atlantic pacific and Indian oceans plus the Mediterranean and the red sea and the south china sea.

The tech giants like to frame these vast environmentally disruptive infrastructure projects as civilization-enhancing largesse on their part. Still, they’re also shareholder companies who know perfectly well that increasing the number of human beings online is the only way they can continue to grow.

Hang on a second, what about Starlink? Isn’t our old mate Elon about to make the internet wireless any day now? For now, cable is the cheapest and most efficient means of fast-eating vast data packets over incredibly long distances. Even normally bullish Musk says Starlink is only aimed at people who don’t presently enjoy access to high-speed fiber, but who knows how that’ll pan out in a decade or two.

For now, the future is very much undersea cables. This summer, Google and Facebook announced a joint initiative to build an undersea cable named Apricot Apricot that would link up Singapore, Japan, Guam, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Indonesia by 2024.

The most extended subaquatic cable ever, a 45,000-kilometer-billion-dollar monster called to Africa that will link up 33 nations, was just bankrolled by a Facebook-led consortium. What do you think humankind’s ingenious submarine network one day looks as obsolete as the telegraph? Let us know in the comments.